Self-published by the author through

Multimedia Design Limited.

Multimedia Design Limited

13 St Matthews Street

Ipswich IP1 3EL

Typeset in Gill Sans, Sovereign, Times,

English 111 Vivace and Brush Script. Printed with Microsoft Word on the Lexmark

C532. Illustrations and tables designed using Corel Draw, Microsoft Excel,

Microsoft Photo Editor, Ulead PhotoImpact and Bryce. Cover design by the

author. Cover printed on the Canon iP4200.

Thanks to:

Nan P and the family; Paul; Clive, Mez, Jelly

and the Gang; Uncle Frank & the Lees; Jeremy and Kelvin; Cathie, Duncan

& Emerald; and Suzanne, Fiona, Matt W & Matt P.

This publication may be liberally lent,

re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated fully according to the wish of the

purchaser

Contents

Table of Figures. 5

What is Psychology?. 7

Part One: Transactional Analysis. 7

Parent, Adult, Child. 8

Transactional Analysis. 9

Transactions. 14

Part Two: Transactional Synthesis. 21

Ratios. 21

Common Sense. 26

Introduction. 26

Transactional

Analysis. 36

Typing the Individual 42

The Taxonomy of Characteristics. 51

Pride Vs. Humility. 52

... And Kindness. 58

Characteristic Assignment 62

Typing the Actor 68

Component Ratios. 74

Typing the Author 81

Transactional

Synthesis. 90

Sex And Gender 92

Typing the Role. 93

The Domain of Work. 96

The Domain of Play. 104

The Domain of Adventure. 112

Transactions. 125

Introduction. 125

Overlapping Transactions I: Balanced (Touching) 131

Overlapping Transactions II: Unbalanced (Inapposite) 135

Complementary Transactions: Moving.. 140

Games, Rites And

Scripts. 141

Conclusion. 146

Hollywood.. 156

Film Part1: the US. 156

Casting. 160

Conscience. 170

Film Part II: the US. 171

Consciences. 177

Film Part III: the UK.. 178

Appendix One. 184

Seven Deadly Sins. 184

APPENDIX TWO.. 186

Shallow Transactions. 186

APPENDIX THREE. 187

Actor’s Typing. 187

Table of Figures

Figure 1: Transactional Analysis. 36

Figure 2: Mapping from three spatial axes of x, y,

z to three abstract axes. 37

Figure 3: Looking inward. Mapping to three

abstract internal axes. 38

Figure 4: Within the mind we see the white light

of conscience concentric to the mind of the individual as well as to the mind

of Humanity. 39

Figure 5: The mind starts to take on Character. 40

Figure 6: The mature diagram shows the three axes

of mind for the individual and all society, extending through the unconscious

and into the conscience. 42

Figure 7: One avenue of further investigation:, by

subgrouping the characteristics. 45

Figure 8: A second avenue of further

investigation: 45

Figure 9: Reactions to the world vary in

importance but just as clearly also vary by type. 48

Figure 10: Key events are common to many people’s. 49

Figure 11: Principles of Psychology both raise and

address principles of Philosophy. 62

Figure 12: Professor Eysenck mapped four

dimensions to the ancient theory of humours. 63

Figure 13: In three stages, we can divide, compare

and contrast using the principles of a) three divisions, b) paired opposites

and finally c) three gradations. 65

Figure 14: Overlapping three sets gives us the

shaded areas each of which is not one of the three given sets. 66

Figure 15: A pleasing result indicates we are at

the right place on the path but does not indicate a particular way forward. 67

Figure 16: Two ways of viewing two dimensions

seems like four dimensions (and four people-types) when it is really only

three. 67

Figure 17: The paradox of the expression of

‘self’: is it the person or the persona?. 73

Figure 18: Two alternatives, shown bottom and

middle, to represent different personality types, from top. 75

Figure 19: Three examples, showing the problem of

PAC. Some might say the father is greater than the entrepreneur, not lesser. 78

Figure 20: Consideration of the PAC-type will

always show us where the quality lies in our diagrams. 80

Figure 21: Two ways of viewing two dimensions

seems like four dimensions (and four people-types) when it is really only

three. 88

Figure 22: In thought, movement is the norm not

the exception. 90

Figure 23: Men and women think differently though

they are not different. 92

Figure 24: Men and women are oriented toward each

other even moreso than toward God, or themselves. 92

Figure 25: Extending the perimeter cannot be done

physically, so should be done meta-physically. 95

But there is still a problem with the 6:4:2 which throws

theory into question. I cannot easily draw it. It is that 4 component. You will

see what I mean if I draw the ratio (see Figure 26). 96

Figure 27: No single representation of the 6:4:2

configuration seems to be natural. 97

Figure 28: Three dimensions of PAC explored

through shape and a different three dimensions of colour (shown in

black-and-white). 107

Figure 29: Introducing a diagram earlier in time, before

type gets established. 112

Now I can put this together with Figure 29, the

new type of diagram, which will give me the first usage of the new diagram, as

a starting point, below (see figure 30). 113

Figure 31: Holding a point of view all the time,

in all circumstances, is not easy. Sometimes it is easier to see the opposite

point of view. 114

Figure 32: A position which is depressing at the

time (shown by the dotted circle) reaps its rewards in the future (shown by the

smaller circle) 115

Figure 33: The well-adjusted individual contrasts

with the individual who maintains a view which may not be in their own interest

– for good or ill. 117

Figure 34: The transaction that is too commonplace

can become a cliché, as with the womanising politician. 126

Figure 35: Two further types of transactions, so

commonplace as to fall into the class of cliché, are those relating to the

artist and the scientist. 126

Figure 36: Thinking within the mind produces

internal transactions. 127

Figure 37: An overlap may be the best way to

represent the subordinate/ superior relationship from both ways of looking at

it. 134

Figure 38: The three types of transaction:

co-operative, competitive and complementary. (Size differences used only for

convenience of illustration). 135

Figure 39: There is fault on both sides only if

both have departed from the moral centre. 139

Figure 40: The words of the transaction resist

analysis, but they paint a clear picture. 139

Figure 41: The given start point of three

‘mind-sets’ within a containing perimeter. 148

Figure 42: Cognition could lend itself to a

Bicycle Chain metaphor – if we can solve the problems. 148

Figure 43: Trying to reconcile our new

understanding with traditional TA offers a compromise on the way to embracing

a new understanding – rather than assuming the new understanding to be

complete. 151

What is

Psychology?

Part One:

Transactional Analysis

What is psychology and,

more to the point perhaps, what business is it of mine as a computer programmer

to be asking?

From the professional point of view I should

have no reason to be interested - or at least, no more interested than average;

and I could have retrained professionally when I took three years out of my

career to do this kind of work, full-time. But I didn’t take the opportunity

then, and I am unlikely to get it again.

Of course we are all psychologists. Every

time you say something like: “Son, make me a cup of tea, would you?” as opposed

to: “YOU! Give me tea NOW!” or “Please make me a cup of tea,

sunny-bunny; otherwise I’ll scream and scream, and hold my breath till I turn blue!”

then you could be said to be utilising basic psychology. (You will certainly be

more likely to get your tea.) But then what is “non-basic" psychology?

Indeed, given that the alternatives I’ve suggested would hardly even cross most

adult minds, what is “psychology” not?

If you think this is straying into the realms

of philosophy, then I think you are quite right. It is the philosophy of

psychology which concerns us here and now. (I don’t think it should be

vice-versa). I will have to draw from my own experience, but the title here is

not “What is my psychology?”, and it is the right one.

So what is my answer? Simply put, it is that

psychology is an understanding of the mind, based on a combination of the soul,

through our shared conscience, and one’s own free will to choose.

Nothing surprising about that I know (even

from a Computer Programmer), but neither is it a fair summary of quite what I

want to say; so, at the risk of wearing out my welcome straight away, let me

explain just what I mean.

Many years ago, I chanced to read the famous

books about Transactional Analysis. You may even have read them yourself -

‘Games People Play’ and ‘I’m OK, You’re OK’. They were worldwide bestsellers.

They propose a theory based on the observation of three components to the

personality, called the Parent, Adult and Child.

Of course, there are many theories about why

people behave as they do: cognitive; behavioural; neurobiological;

psycho-analytic. Perhaps the most famous of all is Freud’s idea that there were

three components to the mind which he called the id, superego and ego. To my

mind however, this is exactly the same observation as that made by

Eric Berne, which led him to create Transactional Analysis. The names are

different, to reflect a simpler understanding, but the fundamental

misapplication which both Freud and Berne have made is to try and see the mind

as fundamentally an analytical machine, by putting the Adult at it’s centre,

when in fact the seat of the personality is the Parent.

This simple change of viewpoint makes it

possible to see that not only is every mind composed of all three components,

but also that it is composed purely of these three, so that at one

stroke we have found a basis for the mind which is entirely distinct from

either the body - or indeed, the brain.

So, is it merely then a matter of saying that

everyone else is wrong and I am right? If only it were then our job now would

be so much easier! I cannot say that any of the existing theories of psychology

- behavioural, neurobiological, cognitive, transactional analysis, etc. - is wrong.

Indeed, I understand it is generally recognised that they are all appropriate

in their own spheres of expertise. Rather what they are is specialisations of a

general theory, but it is the first such general theory that I am proposing to

set out. As I see it, my job here is a complete declaration of what I would

like to call a discovery, so that you can see as clearly as I the ‘ology’, as

it were, of Psychology.

I will start with a discussion of the three

components in principle so that we can gain an understanding of how the same

characteristics may be manifest in different people. This will allow me to show

how people in action together form transactions which can be analysed,

again with an understanding of the part played by the different components.

From there we can move on to the other half of the theory. By the end, I hope

you will agree with me that this is a discovery; that, like Gravity, it

is a great and simple one; but also that not everything is psychology, so that

after all, there is such a thing as Transactional Analysis - and Synthesis.

Parent, Adult,

Child

To start with the most basic introduction and

so ease ourselves in; what exactly is meant by those terms, ‘Parent’, ‘Adult’

and ‘Child’?

In traditional Transactional Analysis the

distinction is made between child-like, in the sense of spontaneous and

intuitive, and child-ish, in the sense of immature or selfish. One’s

Child component is the source of the former and not the latter. ‘Please

make me a cup of tea, sunny-bunny…’ is not my Child speaking, it is me being

childish.

(Or rather, it is me pretending to be

childish...)

Play-acting; pretence; creativity; these are

the elemental attributes of the Universal Child.

The Adult is the rational, analytical part of

you. In some ways it is the easiest for anyone to grasp simply as IQ. However,

rather like horsepower for a car-engine, IQ indicates only a potential of

brainpower, and not how to best drive the car. One goes to school to be trained

in using the ‘engine’ just as one trains for a car-driving test. But experience

is also needed. To complete the analogy, one wouldn’t take a Formula One car to

the shops.

It is the Parent which is most difficult. In

traditional Transactional Analysis, it would be the mental legacy of one’s own

parenting but again, I think it is so much more than that. My working

definition is experience, gained over time. It is this component which

comprises that indefinable absolute, your spirit. In this sense it is connected

not to the wisdom of our fathers but to the wisdom of our forefathers.

What is the spirit? It’s a question that is

different for everyone. I think the Parent is the area of social

facility. I think that it is formed irrevocably by experience and that,

finally, it is the area of self-knowledge and knowledge about the world. But

what is it, really? Well, maybe that is what we are here to find out.

Transactional

Analysis

I’ve used the intersection between components

to add depth to the descriptions, with colour filling in the essential

character of each component. Based on the three characteristics of experience,

intelligence and emotion, it is beautifully clear to see that the

passionate and creative Child is warm-bloodedly red in character, whilst the intellectual, analytical Adult may be coloured a cool blue.

Meanwhile, as the colour of purity and perfection, we may initially colour the

Parent a neutral, perfect white. (This is the colour that is made when all

other colours are mixed together, of course.)

The table below gives what I hope is a fair

summary both from my own point of view, and from the existing understanding of

TA. Thus, if the Child is emotional, one’s subjective judgement of it would be

good or bad, whereas the criterion would be strength or weakness for the

intellectual Adult, and either short-term or long-term for the effable Parent.

|

Table One

|

|

|

Let’s start with an example.

Characteristics are the fundamental way of describing personality so that, for

example, I might say that my father was volatile, but not ill-tempered.

My friend is talkative, but not trite. I am combative, but

not guileful. In saying this, I am not revealing anything about the

personal circumstances or history of either my father, my friend or myself, but

I am still telling you something about each of us. You now know how we might

behave in a general circumstance; and also something about how we might not

behave.

To apply the theory in practice, we could go

on to see that, where my father is volatile but not ill-tempered, he has a

broad Child because it is self-evident that volatility has an emotional basis.

Similarly, I may guess that combativeness is fundamentally an attribute of the

Adult, because I think I am right. But what about talkativeness? Would that be

primarily an attribute of the emotional Child or of the intellectual Adult?

If we were to view any initial characteristic

as solely a function of the Child then all characteristics would soon

become available to the Child (depending on how non-judgemental we were

prepared to be) and, to take this to its logical conclusion, we would end up

with no characteristics for the Parent.

In order to introduce a meaningful separation

we must redefine the Adult.

Let us return to the car engine analogy. IQ

is like ‘horsepower’ and more horsepower is best; but a Formula One car is

artificially constructed and maintained. Most cars are tailored for comfort

(taxi or limousine), or safety (Volvo or 4 x 4) or for looks (Cabriolet,

Porsche). We know that there are different types of car but is this really only

saying that there are different types of people? In that case we would not be

saying something that was only about the Adult.

The one thing that every engine needs is

fuel. In the same way, your IQ does not function at its best when you are tired

or scared, or when you are elated, for example when drinking alcohol. It best

functions when it has a good, new idea to think about. The Adult benefits from

good, strong ideals in the same way that a car engine benefits from a clean,

steady supply of pure fuel. As much as the Adult is intelligent and clever it

also benefits from being honest and moral. Whilst it is true that the Parent

has the metaphysical quality of the conscience, it is still not better than the

Adult, or Child.

Now, if the moral framework is worked out

intellectually then it means that a far greater range of characteristics may be

assigned to the Adult than simple intelligence. In fact, one’s moral or immoral

nature; one’s honesty, dignity, self-restraint or loyalty; would all be a

function of the Adult rather than the Parental conscience. So, where we would

link the characteristics that are ‘hot’ - spontaneity, passion, creativity,

humourousness - to the emotionalism of the Child, we can now link those that

are ‘cool’ to the intellectualism of the Adult: those I’ve already touched upon

such as honesty, dignity, courage and loyalty.

The realisation that the Adult is as good as

the Parent is the beginning of realising that the Parent is the heart of it,

but we are not there yet. Let me try a different approach, with the Parent

components of actual people, as in the diagram below.

My father is volatile but not ill-tempered.

Excessive volatility - but without other ill effects – indicates no lack of

conscience but simultaneously an excess of ‘hot’ Child and a lack of ‘cool’

Adult. I am the opposite to my father. I am combative but not guileful.

Combativeness combined with guile might make for a treacherous combination but

honest combativeness, like ambition and independence, I would see as part of

the ‘cool’ Adult.

Obviously, you don’t know the people in

question so you can’t instantly tell how fair this assessment is of the three

of us, but it is my friend who is most interesting of the three. My friend is

talkative, and it would (in my view) be a short step for him to becoming trite,

but it is a strength of his part of the conscience which prevents him taking

that small step. In other words, my father, my friend and myself are equals: we

have the same size of mind; but of the three of us, my friend is the better: more

'rounded' and 'well-balanced'.

It is a strength moreover which he needs to

have, day by day. In the sense that it is a struggle, I think it is his

intellectual honesty which forces him to avoid the easy option. Again,

intellect and honesty are aspects of the ‘cool’ Parent. When you don’t steal

because of the fear of getting caught your Child is simply acting in your own

best interests. There is no conflict. Or if you steal and are punished, whether

through being caught or owning up, again there is no conflict. When there is

the temptation to steal which is not taken up, which is resisted, then one is

acting within a moral framework.

My friend knows that talkative is right for

his Child but he has worked out that trite is right for some people but not for

him.

Let us fit this fuller definition for the

Adult into our understanding of the Parent and Child. Well, the Parent is still

clearly separated. (I am fairly clear, as I have said, that one of the defining

differences between the Parent and the other two components is experience.

There is something utterly immutable about the acquisition of experience; you

are born, you live, you die and you can neither exceed that experience, nor

avoid it). In fact, there is something mutable in the Parent which makes the

system work. The Adult and Child are - somehow - infinitely renewable; every

day you are alive is a new day and you can’t ever ‘fill up’ your memory, no

matter how much knowledge you acquire. This is not so, in the Parent. Here,

time passing does make a difference, and the ultimate renewal for the Parent is

death. It may be inconvenient at the time but, on balance, you probably

wouldn't want it any other way!

But still, precisely because of this,

experience is not quite a characteristic in the sense I would like to use it.

Indeed, none of the three fundamental characteristics I have been tempted to

use; neither experience, emotion nor intellect; is unique to human life. A dog

has a heart and a brain and a sense of itself - obviously. Even an ant has some

degree of individuality, since it lives out a life, so what is it that marks

out we people from the animal kingdom?

Well, I may still not be right but I am now

improving my earlier conclusion in suggesting that there are three

characteristics which are endemic to all of us to some degree or another, and

which may mark us out from the animal kingdom. They are: kindness, bravery and

humility.

You’ll notice that I am prepared to go wrong,

as part of my presentation. More than just a dry textbook, I am trying to

include the reader in the reasoning. I hope to share some of the thrill of

discovery in passing on my teaching. Besides, I am combative and stubborn

(A-type trait also) ; so back to kindness, bravery and humility.

For the Adult, the core component I would

propose is courage. It is courage, the willingness to fight and suffer for what

you believe to be right, which binds together mere intellectual knowledge into

a moral framework and which may be seen to form the basis of those

characteristics I've already assessed as Adult: honesty and nobility; or

alternatively, deceitfulness and depravity.

For the Child, I would suggest kindness. Some

might go so far as to say love, and in some ways it is quite tempting. A person

who loves nothing and no-one is inhuman, by any stretch of the imagination, but

love is a big word and it encompasses not only the generalised feeling of

benevolence that a parent has toward a child but also the special feeling that

one (grown-up) adult can have towards another. For this reason, I prefer

kindness to describe the Universal Child.

For the Parent, the characteristic I would

suggest is humility.

The great advantage of having this single

characteristic is that we can observe it alone in both strength and weakness to

extend our understanding of each component. For example, when present in

strength, kindness may result in great compassion for others or, when weak, in

great meanness toward a particular person, so that these may be said to be

characteristics of the Child. Equally, when courage is appropriately placed it

is admirable and even noble, but when misplaced it may be proud or arrogant, so

that these would become characteristics of the Adult.

Now, we know where we stand with courage and

kindness, but the case is rather different with humility. It is notoriously

difficult to define. It is said that a monk was once asked to go on a mission

to all the other orders in the land to find the great strength of each. Upon

his return he went to the head Abbot and, after reeling off a list of the

orders and the characteristic that each had as it’s strength - charity,

piousness, poverty, etc - he ended by saying his own orders name “and we are

the humblest of all!” It makes you smile, of course, because humility is the

one characteristic that recedes quicker, the more quickly you approach it. How

then can we observe strong or weak humility?

I remember when I first began to wonder about

what humility actually was, and found that indeed it is one of the oldest

theological problems. The argument goes back to Thomas Aquinas that pride is

the devil and humility the answer.

Actually, it is like asking what is the

difference between a good and a bad person. Any answer I give is going to fall

short of being satisfying, but let me do my best. Let us say that to be humble

is to act well without hope of eventual reward. There may be eventual

reward, but that is not the basis for the behaviour. An example of this is

giving money to a good cause. Very few of us gives as much as we can whenever

we can, but some do. And some people give nothing, whilst most of us is

probably like me, giving less than they can, and less than they should.

But we are not blind and we carry the burden

of knowing that. You would expect that the person who gives nothing to have to

make up for it eventually, at least to the conscience in their own mind.

Similarly, the person who gives fully will find that they are rewarded

eventually, if they just persevere. There is no especial reward for the rest of

us: those of us who give occasionally and faultily. And no more should there

be. We know that.

So, a person who is able to be humble in many

areas of their life is a person with strong humility - but this may be

contrasted with a person who is very strongly humble in only one area of

life. It is quite tempting to consider that there may be two types of humility;

what we might call social humility, as opposed to individual humility, Except

that, to say there are two types is like saying that there are two types of

people; good ones and bad ones, all over again. It may be so, but we are not

the people who should make that judgement, There are likely as many types of

humility as there are types of people.

We are not attempting - indeed we reject in

principle - a perfect Parent. It is instructive to consider the choice of

colour we have made for the Parent. We have two primary colours in red and blue

(or cyan and magenta), and this implies a third. It would give us the choice of

yellow or green, in place of white to capture the essence of the Parent. Notice

that we were not wrong in thinking of the Parent as white: this is the colour

when all three of the components are mixed. It is just that that may not be the

best way of looking at the Parent.

Green is a good choice being both the colour

of nature and the colour of inexperience. Yellow is an equally good choice

being the colour not of a negative – inexperience – but of a true positive –

happiness. Of the two, I think we can agree that perfection is all well and

good, but we would lose nothing by putting it to one side in place of pragmatic

happiness.

Naturalness as a characteristic is also

desirable and may be something that is enhanced by experience, but I think it

is also a bit too close to the Child’s spontaneity to be the best choice. Yet

notice that courage is an attribute of the Adult, yet yellow (which is the

traditional emblem for the opposite of courage) is now not an attribute of the

Adult. What an interesting finding. Would we be surprised to find that

cowardice is not one of the ‘deadly sins’ of conscience? I think we should not

be.

However much the shame (of the Child) wounds

us, it is not a crime to fail to live up to the ideal of the hero. As a

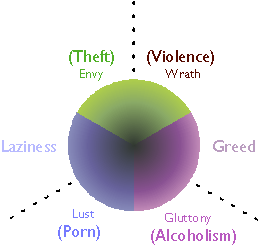

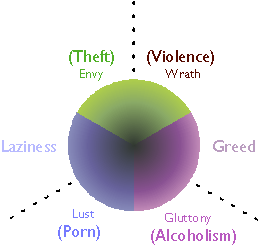

reminder, the Seven Deadly Sins, were: hate, lust, envy, laziness, gluttony and

avarice. I am very happy that the final colour with which I have ended up for

the Parent is the colour of happiness itself. These three primary colours may

be mixed to make all of the infinite hues under the Sun. All are necessary, and

neither one may be said to be better than the others.

This is the ultimate

development of our initial discovery: the point at which the diagram reaches

maturity, for now the mind is centred on the conscience (the white at it’s

heart), which is the only appropriate psychological view.

This mind is indeed linked to those of our

forefathers, but it does not contain them, for they are not lesser. Rather, the

mind of the individual is connected to the infinite unity within it, whether

one calls that the conscience; the subconscious; the unconscious; the spirit;

or as some would: religion.

Remember that religion has traditionally seen

pride as one of the deadly sins. I cannot agree with that. I left pride

(arrogance?) out of the list of deadly sins deliberately, giving six in total.

These could all be mapped to the component of the Parent but more interesting

is to consider whether they can be mapped equally around the circle which would

straightforwardly divide into six. As a fun exercise, you might like to try

this for yourself before looking at my answer in the Appendix at the end of the

book.

Now I don’t know exactly how many

characteristics there are in the English language - probably thousands.

Gregarious, greedy, grave, great-hearted, green, grotesque, grouchy,

grovelling, grand, grandiose, grandiloquent, and so on; but in my own judgement

I have tried to develop the table of opposing characteristics into a continuum

to give a better flavour of each component, as I understand it.

|

Table Two

|

|

|

In fact, you may be interested to know that

the assignment of traits to personality types, whether to groups of three, four

nine or twelve types, is a long-established aim for those who would grasp the

mind. It goes back to the theory of the four humours; melancholy, sanguine,

choleric and phlegmatic in 2AD, and it may be found in fields as diverse as

Chinese medicine (nine components) and the twelve signs of the Zodiac.

It is time to move on to the area from which

Transactional Analysis takes its name. What is a transaction?

Transactions

A transaction is simply an interaction of any

kind between a person and the outside world, or a person and another person, or

even between one person and a group of people, where the start (or stimulus)

matches the end (or response). For our purposes, a transaction may be broad, or

it may be deep, or it may be shallow.

A broad transaction would be one that takes

place across the range, so to speak, of the personality, either through a long

period of time or in a wide range of circumstances.

A deep transaction, as the name implies,

would be one that involved the most profound part of oneself; for instance, a

core belief; being either very painful or very pleasurable. All other

transactions would then be shallow, although this is not meant to be

pejorative, since between two people who don’t know each other very well or who

have no particular reason to care about each other, a shallow transaction would

be entirely appropriate.

I have three examples for us. One is both

pretty and true, and one is simply shallow. The other is not pretty but it is

true. These are examples drawn from my own experience.

I’ve mentioned my father already in passing,

but there is also a story to tell, about both of us.

My Dad died almost ten years ago. My mother

has since remarried, but the Peter Cross I remember was a man of huge industry

and seemingly bottomless cheerfulness. County Councillor and Chairman of the

Board of School Governors, as well as the man’s man who introduced me to Poker

and Squash, I knew him to be utterly fearless, given to sentiment, alongside

his volatility. yet rarely gentle. This was a man of whom I could say when I

was eighteen ‘forgive, but never, ever forget’.

When I was born he was a pilot for British

Airways (BEA as then was) having learnt to fly helicopters in the Navy. He

didn’t talk much about it, but he was from a working class background and his

parents - my grandparents - had long been divorced. Unprepossessing and

unglamorous as they seemed to my youthful eyes, it was astonishing to discover

that they used to call my grandfather “the monster”; and that his drunken

violence lasted until my father (who always carried a bit of weight) got old

enough to physically restrain him by sitting on his chest.

Before they had any of their six children, my

father and mother decided that my father would be the sole disciplinarian in

the house, and it was a decision that they stuck to throughout their married

life. I only found this out later. My parents always presented a united front

to their children - or rather I think now, they always hid their united front

from us - and we had no way of knowing that only my father’s sense of justice

held sway.

I worked this out for myself when I was

eighteen. Up to that point, my father was simply unfair, and I might have hated

him for it, seeking the combat. However, one day, I was playing with a plastic

bucket in the back garden, idly dropping a big stone into it again and again,

when the inevitable happened. The stone caught the side of the bucket and went

straight through, holing it.

What to tell my father? I could tell him the

truth but I knew from long experience that he hated that kind of spiritless

vandalism. Or, I could tell a complete lie. If I said I had just plain lost my

temper, kicking the bucket and so holing it, then that’s the sort of thing he

could have seen himself doing. The trouble was, it was utterly out of character

for me. What if he realised my manipulation? I loathed that sort of guile

myself as much as he loathed spiritlessness but, after all that had happened,

it didn’t seem so bad.

And when I did, it was like a revelation! Not

only did he take the lie completely at face value but he even didn’t mind about

the bucket! It was almost as if he was relieved that I was human, like him. I

remember thinking to myself, how could you ever hate a man whose sense of

justice was so simple! From then on, until he died in my late twenties,

all of the heat went out of our relationship. But the transaction which was for

me so deep and broad was one of painful imbalance, for I am convinced that, for

my father, it was no more so than any other transaction that day.

The story, and even more the diagram above,

seem to point to a mighty judgement as indeed I promised myself, in my

eighteenth year. Yet I find that that is the last thing I would wish for now,

as I try to grasp the difference between my father and the man, Peter Cross,

not to mention my own question. There is something self-defeating in the idea

that what I might be doing now, here where I am most at home is no more than

the obverse of what my father would have done, in his own home.

In that case, the point of view from which I

would wish to look at this transaction is not that I am better than my

father, as his early life will illustrate. I did promise not to introduce my

own psychology into the subject but not to do so now would not seem quite

honest, so I will try to keep it limited. Notice then that one of the things

about this diagram is that I have quite naturally drawn it with my Parent

facing that of my father, even though I was the child.

In the world that I aspire to live in, where

the punishment of one’s own conscience is always equal to the gravest crime

that can possibly be committed, the greatest sin can sometimes seem to be to

act inappropriately to the situation - wasteful, as it were, both of the

opportunity of circumstances and the potential of the individual. For this

reason, it would be complete anathema to me to consider that my own behaviour might

be utterly inappropriate to the situation; yet here I seem to be proposing just

that, in seeing myself as Parent in relation to my own father.

As I said above, all of the heat went out of

our relationship following this one transaction, but why was the heat there in

the first place? Well, the smaller circle that I drew above represents the role

I was trying to take, just as someone might seek a supporting role in a drama

rather than the lead, but our circles are, in reality, the same size and, from

the point of view of analysis, this is the understanding which I would like to

reach.

When I was expecting my father to be fair, in

the sense that I understood it, I thought his sense of justice must be terribly

complicated and, in the intermediate diagram above, we can see where this

friction was incurred between us for all those years, in the red area, where my

Child is too close to him.

All my life the problems which have been most

difficult for me; the ones which one would have thought must have the most

complex, intransigent and complicated solutions, have often turned out to be

the most awesomely simple, should one be prepared to see it that way.

So it was when I quietly understood that my

father’s sense of justice, far from being as monolithically complex as I had

come to expect, was actually so simple. When I realised that it was not my

mother and my father, it was just my father, I felt as much sympathy as blame

for him, and I would no more seek his understanding of my inner Child than I

would inflict my demanding complexity onto him. We were not as close as I would

have liked us to be, but we had been too close before, so to speak, and this

was more comfortable, for me at least.

The final diagram above, I think, shows both

the immediate effect of the incident I’ve related and my final position with

respect to my father. The orientation had changed away from conflict with him

because I knew deep down inside that I would never be my father, even if I were

to have him for a father, all over again.

In fact, after this I became a bit of a

defender of my Dad to my elder brothers. They, of course, had it worse than me,

just as my younger brother had it much better, but I felt that, whatever my Dad

had done to us, it had not involved his conscience. He learned his sense of

fair play from the Navy, and it was a Naval strictness that he tried to apply

at home.

Now, let’s move on to an example which I

think is pretty as well as true: the point of saying to another person “I love

you”.

Whereas one’s family is possibly not a matter

of personal choice - on either side - clearly this is a matter of both free

will and mutual choice. That is why I should normally expect broad transactions

of the former and deep transactions of the latter, however I am not married and

I have yet to say this for myself. Instead then, let me tell you about another

thing for which I have felt a similar feeling; the writings of John O’Hara.

I think he is one of the great American

writers of the Twentieth Century. Whereas for me, Fitzgerald is a little light

and Faulkner a little heavy, this is the basis on which I would say that

Steinbeck, Hemingway and O’Hara are all of a parity, so that were we to make

the leap, Hemingway’s spare, muscular prose would mark him out as the Adult

compared to Steinbeck’s Child-like love of people and, of the three, it would

be O’Hara who was the most overtly Parental, to my taste.

His metier was the short story, of which he

wrote some four hundred; along with fourteen novels. Even though he enjoyed

great commercial success until he died in 1971, I think there are only two of

his books still in print. I’ve tried to read all of them.

That may say more about me than about O’Hara,

of course, but the very first book I read (‘The Collected Stories of John

O’Hara’; ISBN 0 330 29605 1) came with an introduction about his way with

dialogue. This brings us back to the subject because a conversation is a

transaction, and the excerpt that I reproduce represents one that is worthy of

examination here.

Have a look, if you will.

|

EXTRACTED FROM

‘JAMES FRANCIS AND THE STAR’, BY JOHN O’HARA

In the five or six paragraphs preceding this extract we have

learnt that James Francis is a successful Hollywood screenwriter and that he

is a patron, as well as a friend, to a struggling, would-be film-star, called

Rod Fulton. Francis has just given Fulton a long lecture telling him to watch

his weight, and Fulton replies:

"Well fortunately I like to take exercise, and if I never had

another drink I wouldn't miss it."

"Fortunately for me, my living doesn't depend on how I

look."

"You do all right with the dames."

"Some dames," said James Francis. "If you can't

make a score in this town the next stop is Tahiti. Or PortSaid. Or maybe a

lamasery in Thibet."

"What do they have there?"

"What they don't have is dames."

"Oh," said Rod. "What did you say that was?"

"A lamasery. The same as a monastery."

"Do you think I ought to read more, Jimmy?"

"Well it wouldn't hurt you to try. But you don't have to.

Some directors would rather you didn't. But some of them don't read any more

than they have to."

"I wish I could have been a writer."

"I wish I could have been a good one," said James

Francis. "But failing that, I can be a fat one."

"Well, you're getting there, slowly by degrees. You're the

one ought to start taking the exercise, Jimmy. I mean it."

"Oh one of these days I'm going to buy a fly swatter."

"A fly swatter? You mean a tennis racket?"

"No I mean a fly swatter."

"You bastard, I never know when you're ribbing me," said

Rod Fulton.

|

What I think O’Hara is concerned to show us

in this conversation is that these two men are peers, for the same reason I

wanted to explain who are O’Hara’s peers. Clearly there is a potential

imbalance of power in the relationship between patron and protégé and O’Hara

feels that the best way to establish that this isn’t the case is with a direct

conversation, but its a good transaction for us because it has a dramatic

climax, a resolution, and a conclusion.

Rod begins with an open comment about himself

- this is one of the most appealing things about O'Hara's characters in

conversation. It is a form of honesty. They are open and frank, even leaving

themselves vulnerable. And indeed, James Francis' reply "...my living

doesn't depend on how I look." does contain a slight rebuke. Rod's next

comment, if slightly gauche, is well -intentioned "You do all right with

the dames". Now the brash comment is corrected by an extremely

sophisticated remark by the writer "Some dames. If you can't make a score

in this town the next stop is Tahiti. Or Port Said. Or maybe a lamasery in

Thibet." He first mentions Tahiti, showing an awareness of its unusual

sexual culture; he then mentions Port Said, a notorious Western Gomorrah; and

finally - the coup-de-grace - he trumps the previous two with a glib spiritual

reference. It's a bit too smart for Francis' own good though, his creator is

telling us this is an experienced man; perhaps dissolute.

As Rod makes a straight factual enquiry

"what do they have there?" we realise he has not yet grasped the

point. James Francis now shows the nature of the friendship because he finds a

way to point this out to the actor without offending his dignity "What

they don't have is dames." In turning the question around James is gently,

and not without humour, pointing out his friend's ignorance.

And now we come to the climax of the

conversation, the point of open acknowledgement of James Francis' current

superiority to which the conversation has been working up. Rod Fulton not only

asks James for a judgement but he specifically acknowledges the relation by the

use of his name "Do you think I ought to read more, Jimmy?" It is a

crisis of sorts because James Francis can assert that superiority once and for

all if he wants; but if he does, then this will cease to be a relationship of

equals because he will then have refused the offer of trust that Rod is making.

And James Francis makes exactly the right

response. He defuses the situation with a gentle “Well, it wouldn’t hurt you to

try. You don’t have to.” Offering a patronly warning of “Some directors would

rather you didn’t” then even redirecting the sting of that with the acid “But

some of them don't read any more than they have to”.

Following this climax, the tenor of the

conversation changes. Firstly, in acknowledgement of his reply Rod makes the

flattering(because almost certainly not true)comment that he'd like to have

done James' job. James doesn't acknowledge the compliment (probably feeling

patronised - he knows he’s bright) but he begins to end the conversation with a

light-hearted reference to the early subject of his weight. Again however,

Fulton displays his mettle, and although his over-Parenting of James is not as

pleasing as the former exchange ('You really should get some exercise. I mean

it, Jimmy!') the mere fact that he knows it is appropriate, is enough. The

fragile equality that the two men have established is underlined by the rough

humour which O’Hara determines should be the end of the exchange.

We must move on from the specific to the

general. We are coming to the end of this brief introduction to TA and, in the

final section, I want to concentrate on a shallow transaction. I will say that

it is always the broad and deep transactions which are most rewarding to the participants,

and most tempting to us as observers. In being emotionally moving, they can

have the appeal of a psychoactive drug, but sadly, such that are genuine will

be few and far between. And as with drugs, the apparent allure of glamour may

easily turn out to be hollow, for which reason, it would always be better to be

satisfied with a shallow transaction that is genuine than with anything which

is not.

The shallow example I have in mind comes from

my work, where I was recently asked to program a service. The service is used

by a Company for recruitment. It requests graduates to answer a series of

questions about themselves by pressing numbers on a telephone keypad, from

which the Company hopes to gather together a personality-profile of the

applicant.

Supposedly, there are no right or wrong

answers, so the applicant is encouraged to answer both honestly and

spontaneously, through a time-limit. Here are three examples of the fifty-or-so

questions:

“I want my co-employees to be my friends”

“I make it a point to learn the names of all

the people I meet”

“I am a highly-disciplined person”

Now, I was not told so but I believe that the

basis of these profiles is the empirical observation of Parent, Adult and Child

types. So, on a scale of 1-5, if five is strongly like that, three is no more

than averagely inclined, and 1 is very much not that way, what would

your responses to the above questions be?

Well, I find it very hard to discipline

someone if I think they won’t like me for it so I would be a five on the first

one. I’m terrible with names so I would be a one on the next, but I am very

ambitious when it comes to work so I would rate myself as five on the third

one, as with the first.

Perhaps you would like to try a little test.

Pretend you had to assess each of these statements as relating to one and only

one of the three components, P, A or C, and see if you can decide, in each

case, which one it would be. Using this understanding, you could even analyse

your own answers, if you gave them. I’ll be giving you a big clue if I say that

the second word of each sentence is highly significant, given that the

emotional Child relates to desire, the intellectual Adult to belief and the

pragmatic Parent to actual practise, so do it now, if you want to.

I will be using my responses of 5, 1 and 5

later. So, in the first case, “I want my co-employees to be my friends”, strong

agreement (or disagreement) with this would be more likely through the Child

than through either the Parent or Adult.

In the next case, the second statement is

also about oneself in relation to other people but, “I make it a point to learn

the names of all the people I meet” is an offer rather than a demand, showing

both social awareness and commitment. (The word ‘learn’ might momentarily make

us tend toward the intellectual Adult, but the practise implied in ‘I

make’seems to tip the balance,) Agreement with this statement, rather than

disagreement, would indicate the Parent component in operation.

Finally, the third statement is about oneself

in general: “I am a highly-disciplined person”. Now, here the trait of

discipline has already been identified as strongly indicative of the Adult, and

the certain belief of “I am” adds further weight to this.

Did you come to the same conclusion of Child,

Parent and Adult for the three statements, respectively? These personality

tests are increasingly common and I have come across them a number of times in

job interviews myself. They seem to work. For instance, on the basis of my

response to the three questions (strong agreement, strong disagreement and

strong agreement) my Adult and Child components would be very strong whilst my

Parent would be very weak. Whilst that might be a harsh assessment of the

person writing it is not, I think, an unfair comment on me in my role at work.

Notice how shallow is this. There is

ambiguity about the significance of each of the statements, and uncertainty

about the significance of the answers. “there are no right or wrong answers”

and the time limit is needed.

But what would be much better would be to

have the theory behind the test explained so that both employer and employee

can benefit fairly from the results. This leads me on to Part Two where we find

out the differences and the parities of the person with the role.

Part Two: Transactional

Synthesis

The analytical aspects

of Transactional Analaysis can take us so far, but they are only half the

answer. For the other half, we need to balance analysis with synthesis,

which is why we are still only halfway through the job in hand. It takes us

onto entirely new ground.

Ratios

Clearly, the ideal is to have all three

components in perfect balance, perfectly expressed at all times. Let me be

absolutely clear about this: there is no excuse. Anything short of the absolute

ideal cannot be tolerated.

Meanwhile, let’s acknowledge that computer

programmers are not perfect.

I acknowledged that I have a weak Parent in

my role as a Computer Programmer, but let us consider the possibility that it

is the role of Computer Programmer which constrains my natural Parent.

Perhaps. Or perhaps I am very lucky. I can

tell someone everything I know about psychology far more easily than I could

teach others about computer programming; and my judgement was that no-one would

pay for me to do this writing - at least, not as well as leaving me my freedom.

Computer Programming may not be perfect, but

it is enough, and that is true not only of me, but also of anyone who

fulfills the same role as I do, at work. We are all adequately described

by the left-hand-side of the above diagram; where, relatively, the Adult is a

dominant component. Other people, who subject their own imperfection to a

differently-imperfect work-role, would best be described by one of the

other two diagrams, where the Parent and Child respectively are dominant.

As we now know, the principle of three

components applies to everyone, everywhere, so it should be possible to split

the whole of society into similar groups. For example, I would think that one

can divide between those professionals in Government and Church for the

Parental type; against Arts and Entertainments for the Child, secondly; as both

against the equal third of Science and Academia, for the Adult.

A person with a large intuitive and creative

bent - a person with a big Child - would accordingly be an artistic type. A

person with a definite intellectual or analytical mien; that is, a strong

Adult; would have a scientific, academic mindset; and an example of a person

with an extended Parent might be a figure in authority, such as a doctor or a

policeman. Or a politician.

Note that in this synthetic case, we

can still not assume that the person with an extended Parent is better

than the other two types. They may be better supported - or equivalently

constrained; they may carry greater responsibility, or have greater freedom;

but only fate will prove whether an actual individual is better, or not; so

that in the case of the example, these three are fully and fairly, peers.

In determining the ratio of components, we do

not differentiate between the highly talented fine artist, such as

Michelangelo, and the jobbing artisan, such as a professional book illustrator.

That is because there may be no difference in the ratio. The difference

in overall quality of mind can only be reflected in all three components now;

in the overall size of the circle, through its radius. We have no way to

quantify that except by the subjective recognition that Michelangelo is no

better than Einstein say, or Abe Lincoln; but that these really are the very

best of men.

That said, we can see the actuality of this

in quite a different circumstance. The very fact that the quality of mind is

hidden when there is an imbalance of components implies that it is not hidden

when there is not an imbalance. In other words we can consider a fourth type of

person, different to all three of the above, but still equal, because they

manifest in their professional life an equal mix of each of three components.

Such a person might be the entrepreneur who sees their own business through

from startup to thriving conglomerate. They might simply be the good father,

raising a healthy and happy family; or if they are very wise right from birth,

they might be recognised as a saint in their own lifetime, like Mother Theresa.

This would be the PAC-type. Plainly, there

would be many paths to the eventual realisation of oneself in this way, but the

objective of each of us, as well as the comparison of Lincoln, Einstein and

Michelangelo at the end of their respective, very different, paths,

would be of this type.

Now we can mathematically permutate the first

three professional categories we’ve discovered. If the types of artist,

scientist and politician may be denoted as ‘Cap’ (dominant Child,

secondary-equal Adult & Parent), ‘Apc’ and ‘Pac’, then we can extrapolate

the existence of types ‘CPa’ (dominant-equal Child-Parent, secondary Adult),

‘APc’ and ‘ACp’ to give us a further three types; seven in all. By extension,

in terms of the professions we might observe that an APc-type would make a good

policeman say, being an authoritarion and socially-minded figure. The PCa-type,

being a caring, intuitive, responsible person might correspond to the social

worker, and the ACp-type, as an individualistic, independent, adventurous type,

could correspond to the journalist or, to come back to it again, the computer

programmer.

Finally, from a single imbalance between one

component and the other two, we could go to an imbalance between all three

components, described as ACp (dominant Adult, significant Child,

notional Parent), APc, CAp, CPa, PCa and PAc.

Again, it is difficult to look at the quantitative differences whilst ignoring

the qualitative differences but, with the broadest of brushes, I might try to

differentiate between the architect who brings discipline to his craft as an ACp-type,

as opposed to the physicist, who brings intellectual judgement to his search

for understanding (APc); the fashion designer, who seeks to express a

personal and internal understanding (CAp) as against the comedian, who

seeks an expedient expression of his eccentric perspective (CPa); in

contrast again with the fully-realised world-view, intuitively on the side of

the priest (PCa), and intellectually, on the side of the Judge (Pac).

I say ‘finally’ because I think this is as

far as we can reasonably go. I have perhaps overstretched my own experience in

assigning roles to all of these ratios. I think it is fair to say that those

which I have assigned to the dominant P-character: policeman, social worker,

judge and priest, are all careers which require a degree of social

sophistication, whereas designer, physicist, architect, comedian and

journalist, perhaps clearly require a more innate manifestation. From my own

experience however, I would find it hard to say for sure whether an architect

really is less creative generally than a journalist, or more.

|

|

Finally also, this third stage is a logical

interpolation rather than a strictly-derived mathematical permutation, derived

from equality. I’ve tried to recognise this by splitting the group into three

and nine to visually contrast the extreme of the first three with the evident

parity of the second nine. I've also had to leave out the PAC-type. It's very

hard to see this as just another type.

We saw some of the problems of grouping

characteristics in Table Two of the first part. This had led us to consider the

existing sets of characteristics, including the Zodiac. Here we were looking

for new knowledge and instead we have stumbled across one of the oldest

theories of human nature of all. I can't comment on the parallel myself because

I’ve no prior knowledge of astrology with which to compare but, as an outsider,

it does seem to me that the Zodiac signs are typically described in terms of

characteristics, and it would be a very easy experiment to ask someone

knowledgeable about how closely or otherwise the theory coincides with the

observed.

So when I said that the transaction above was

shallow, this is how I meant it: that the Company would do as well to ask it’s

applicant what star-sign they are as it would to ask them fifty questions of

the sort I was quoting. Not at all a bad idea, in some ways, but it is a

disappointingly small conclusion. We set out to find something brand new and

instead we have found something very old indeed, and in many people’s view,

thoroughly used up. Have I led us down a blind alley? We have analysed the

theoretical Parent, and we have “created” the synthetic Parent, so where is

there left for us to go? If it really was a trip down a cul-de-sac finishing up

at a dead-end, then there is no way to start us off again.

Except backwards.

Common Sense

Introduction

The purpose of this book is to represent the theory of psychology. Whatever

its particular faults or virtues, I believe some form of this book is

inevitable. The description of psychology it contains is based on one, single,

inevitable idea: a realisation of what the mind is; an idea that is simple, and

yet one which turns out to be not so easy.

The question therefore is not whether

the theory is right; it is. The real question is, is it explained adequately?

What I would like to do is to show how it applies to the huge diversity of

human beings that exists - that is, to the diversity of which I am aware. In

taking on the subject of human nature, I am naturally limited to my personal

experience of it. However, that may be a little wider than one might at first

think, since what I can do is to take examples not so much from direct

experience or from a psychiatrist's textbook, but from film, TV, books and

history. Our shared cultural heritage, from Shakespeare to Hollywood; from Star

Trek to Jim Morrison; from St Augustine to Richard Nixon; from John Steinbeck

to Herman Wouk; is a vast store of information about human nature; one upon

which it is perfectly valid to draw.

To say this is to acknowledge the

limits of what is possible as well as to set out the scope of my ambition.

There may be readers of this book who have never seen the original Star Trek

series, or who have yet to read a nineteenth century novel. It is perfectly

possible that a white, middle-aged, middle-class male who had lived all his

life in England could never have heard of at least three of the names I mentioned

above. But one can see a film after reading the review, as well as before; and

you can read and understand this book with nothing more than your own good

sense. If, like me at eighteen, you remember the feeling of knowing everything

and nothing both at once, then this is the book for that age; for the general

reader, on the threshold of personhood.

The claim is that there is one and only

one central idea at the heart of this work, from which everything else is

devolved. It's an unusually strong claim - things are not usually quite so neat

- so let's see exactly what it means. It means that,

once the initial premise is described, everything else should follow as a

matter of course. It becomes an explanation, not an argument. To follow an

argument one might feel the need for a background training in psychology, or at

least an academic training. To follow an explanation needs only a basic

experience of people; that, and the desire.

The reason for you to have such a

desire with this book is the same as with any book: it is to get to the end so

that you know what happens.

It is an exciting trend in modern

non-fiction. The publishers Fourth Estate are one of its pioneers. Books like

‘Longitude’, ‘Fermat’s Last Theorem’, ‘The Man Who Loved Only Numbers’ and more,

take the liberty of treating the reader as an equal whilst telling a story the

plot of which is information-driven, rather than character-driven. It is my

aspiration to match their success. Because I think this explanation – if I can

do it justice – has the most exciting plot I know. One which has fascinated me

for 20 years.

But more than anything else, this book

is a fait accompli. Once you have read it, you will know it. I hope you

do read it, for that reason, but I am under no illusions: I have set you no

easy task.

Everyone is born with a conscience. And

it is the same conscience for everybody. The ‘collective unconscious’ is

therefore also the conscience.

The conscience cannot tell you what to

do for the best, however: it can only tell you when you have done wrong. This

means, the individual must find out what is right or wrong for him or herself;

which gives a starting point, from whence one never stops acquiring experience,

before ultimately and eventually reaching one’s destiny, which has been fought

for, and loved.

No matter whom you are, no matter what

you do, no matter where in the world you live, all of us have this in common:

the point of each of our lives was, or is, to acquire experience, without going

against conscience, and so reach our destiny.

It is not much of a theory, you might

be forgiven for thinking. I certainly thought that initially. I was afraid I

might end up as a symbol for political correctness. But hang on; there are a

couple of things to note already. We are coming away from the idea of the

collective unconscious as an arbitrary, historical force, and looking to

conscience, as a moral force in its own right. Also, we are identifying a

non-materialistic element: experience, that is radically different to the

material world, which is caught up in time. Unlike every aspect of the physical

world which is bounded by time, when you go to sleep you have absolutely no

sensation of time passing. Why is that?

And most important of all, if you have

a destiny, then others who come after you will, too. And so did others still,

who have preceded you.

In the 1890 book, the Principles of

Psychology, William James laid the groundwork that led, presumably, to Jung’s

creation of the ‘Collective Unconscious’. In his preface he argued that:

…metaphysics falls outside the

province of this book. This book, assuming that thoughts and feelings exist and

are vehicles of knowledge, thereupon contends that psychology when she has

ascertained the empirical correlation of the various sorts of thought or feeling

with definite conditions of the brain, can go no farther -- can go no farther,

that is, as a, natural science. If she goes farther she becomes metaphysical.

All attempts to explain our phenomenally given thoughts

as products of deeper-lying entities (whether the latter be named

'Soul,' 'Transcendental Ego,' 'Ideas,' or 'Elementary Units of Consciousness')

are metaphysical. This book consequently rejects both the associationist

and the spiritualist theories…

The emphasis on the word ‘explain’ is

James’. I am sure that James knew as well as you and I do that his mind

‘contains’ (more exactly: is coincident with) the minds of others, just as mine

does and just as our children’s will. This is not something that needs

any explanation (if any were possible) and it is not something I am explaining.

But given that, there is so much more that one can go on to say.

There are rules which govern the mind

as a purely metaphysical concept, separate from the body and the brain. These

rules are in addition to any creed, religion or faith. Religious faith is

stronger than the rules so we cannot call them laws. But we cannot aspire to a

logical view of ourselves without wondering what these rules might be. By

putting the word in italics, William James did not mean to deprecate our wish

to wonder, and I have already gone beyond merely doing that.

I have been struggling to contain

myself to a single book. I suspect the new reader will find my writing a

confusing combination of wild and daring leaps into the unknown interspersed

with obvious and patronising homilies. It is a long book, maybe, but at least

it is only one. Everybody has one book in them, it is said. I care enough about

it to try and live up to that maxim.

By way of a starting point, what I

would like to do is to take actual people and show how this generalisation may

be seen to apply to them. At first glance it is far from obvious that it

adequately describes a professional footballer, or an IRA terrorist, or an

alcoholic labourer. Even if it were, would it then be apparent that it applies

to John Maynard Keynes; Glenn Miller; Ho Chi-Minh; or Captain Lawrence Oates of

the Scott expedition? My task will be to show so.

The first problem is how to find

individuals who are representative for discussion. Who can we select as

representative of the range and depth of humanity? Well, it might be easier

than it looks if we are prepared to make use of the classical divides between

people. For example, everyone - absolutely everyone and anyone - is a mixture

of both good and bad. However, we can take the group of all good people and say

that Gandhi is a better representative of good than Hitler, whereas Hitler

would be the better representative of all bad people. We would have no

difficulty with the suggestion that Charles Manson, Ronnie Kray, Ferdinand

Marcos or Joe McCarthy all generally had more in common with Hitler than with

Gandhi despite the widest of differences or the closest of similarities in

other respects. The same could be said for Gandhi and Roy Rogers, Albert Einstein,

Winston Churchill or the earlier-mentioned Captain Oates.

There are other divides that we might

use: pride (Napoleon, Joan of Arc, Nietzsche, Thomas More, say) versus humility

(St Francis, Leonardo DaVinci, Abraham Lincoln, Paul McCartney, and so on);

rich versus poor, perhaps; freedom versus justice; or art versus science.

When we talk of a good scientist or a

bad artist it generally refers to a scientist whose technique is good, or an

artist whose taste does not coincide with our own. It's almost always an

aesthetic judgement and not a moral one. Nevertheless, this aesthetic divide

can be just as wide as the moralistic one, with all the communities of science

and technology being separate from all the creative and artistic communities on

the other. From my list I will choose the divide of art versus science because

it so obviously does not correlate with the moral divide of good and bad.

Now we can say that Newton is a better

representative of not only physicists, but of science and technology in general,

than Beethoven, who is in turn, a better representative not only of composers,

but of the entire creative and artistic community, in general. Furthermore, we

can say that both Newton and Beethoven are morally undistinguished, being

neither particularly good nor particularly bad people, possibly in comparison

with each other but certainly in comparison with Hitler or Gandhi. In addition

to that we can also say that Gandhi and Hitler were neither especially artistic

nor especially scientific, both being politicians of a kind, by comparison with

Newton and Beethoven. There is no overlap with the aesthetic divide here,

either.

Consequently, what we have found is a

group of four people who are extremely effective representatives of the scope

of human nature. They may not be perfect, and we have yet to see how valid it

is to do this in the first place, but as a manageable set of ambassadors from

which to examine the scope and variety of the human race, these four are an

extremely good starting point.

Let’s expand the theory: No matter who

you are, no matter what you do, no matter where in the world you live, all of

us has this in common: the point of each of our lives was, or is, to build up a

framework in our minds by which we may understand the world.

If the result of living is the

inevitable accumulation of experience, then we need to be able to process

experience at the same time as we are acquiring it. We need a framework.

If it can be shown that the principle

of a framework adequately describes and differentiates between these four

camps, as represented by the individuals mentioned, then I think I can claim to

have made a real start in demonstrating my initial proposition.

Well, it's no challenge to see Newton

as having spent his life trying to improve his framework of the world since

that is what he is famous for, but how can we see Hitler, in a life dedicated

to the acquisition of power, or Beethoven, in a life dedicated to

self-expression through music, as further trying to understand the world? It depends

on seeing that the framework of understanding one is trying to build up is not

solely intellectual. Of course it may be mainly intellectual, as in the case of

Newton, but it is also partially emotional; and sometimes it is mainly

emotional.

Intellectually one spends one's life

acquiring and discarding beliefs as a result of experience. However, one also

spends a lifetime recording feelings and memories. This learned memory of

feelings corresponds to knowledge of a sort; only subjective to the individual.

It is entirely legitimate to think of it as knowledge because it colours the

judgement and choices of the individual every bit as much as intellectual

knowledge. Thus, instead of seeing the mind as a ladder of singular,

hierarchical beliefs it should be seen as a lattice of interrelated concepts:

not a one-dimensional pyramid with top and bottom but a flexible

two-dimensional framework.

Let's see by example how an emotional

side to the framework may work. Let us say that you are a child of nine or ten

years old and a person you trust completely - say, your mother - tells you to

put your hand in the fire. "Go on, it won't hurt."

Well, you wouldn't, would you? You

probably couldn't. Even if you put out your hand close to the flame, the heat

would scare it away in spite of all you could do. An occurrence like this would

be more likely to lessen trust in your own mother than to make you question

your fear of heat.

So, let's make it a little less simple.

Suppose now you are twenty-eight years old. This time your mother tells you it

will hurt quite a lot, but that an eccentric billionaire has offered ten

million pounds if you will do it. Furthermore, technology is now so advanced

that your hand can be surgically repaired to be as good as new no matter how

badly it is burned. This is a little far-fetched, of course, and you would do

well to be sceptical but let us say you are given whatever evidence will

thoroughly convince you, once and for all. Well, now it should be easy. Now you

just walk up to the fire and without thinking, just plunge your hand into those

flames...

Except even now it wouldn't be that

easy would it? Even though intellectually you have nothing to lose and

everything to gain, you cannot yet cold-bloodedly watch yourself putting your

own hand into a fire. Perhaps you could if the family was starving and

desperate enough, but not when it's just for money. Or perhaps in fact, you

could, just for the money ... but not immediately. You'd need some time to

adjust to the idea; say, a week or so to prepare yourself.

The question is: why do you need time

to adjust to the idea? We have hypothesized that you are thoroughly convinced

intellectually that you can only gain. There must be some other barrier that is

stopping your hand. This is the barrier created by your emotional knowledge, I

would say.

It goes against all your survival

instincts, carefully ingrained and reinforced year upon year throughout

childhood and beyond, to put your hand into the fire. The reason it takes time

to adjust to it is that although it is a minor rearrangement of the

intellectual side of the framework - you only have to be convinced of the

millionaire and the surgery - it is a profound and disturbing rearrangement of

the emotional side of the framework. Not impossible; just difficult, and slow.

Not everyone would come to my

conclusion based on this example. It could be argued that the mind is operating

with just another type of intellectual knowledge on a more basic and thus

perhaps more profound level. It’s an argument that is very difficult to refute

as yet, except empirically: it does not work. If it worked then there would be

no question concerning how the mind works, and no place for this book to fit

in.

An alternative argument against my

conclusion is that the example might be seen as the result of 'mere' instinct;

and indeed, the hand is drawn away from the fire in an instinctive, probably

unconscious, aversion to its heat. The thing to bear in mind however is that if

the example had not cited a reaction that was instinctive then it would not

have appeared to be a universal example. It does not mean that emotional